The whaling industry helped drive industrialization in the 19th century, with whale oil used to light lamps and lubricate machinery. Even after petroleum replaced whale oil as an energy source in the U.S., whaling continued to be part of our cultural imagination and helped develop the idea of an energy industry, said University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign English professor Jamie L. Jones.

Her new book, “Rendered Obsolete: The Afterlife of U.S. Whaling in the Petroleum Age,” examines the influence of a dying industry during the massive energy transition from the organic fuel sources of the 19th century, including whale oil and wood, to the extraction of fossil fuels. The topic is relevant to the current moment, as we consider how to shift away from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources, Jones said.

Courtesy Jamie L. Jones

“As people try to decide how to disengage from a fossil fuel-intensive life, looking at that historical moment can teach us how we might adapt,” she said. “We can’t look around and say this is what the world looks like after fossil fuels. We can say what the world looks like without whale oil. There once were generations of people who didn’t think they could live without it. It offers the opportunity to see how things look after something has ended.”

Different types of energy systems shape culture and our way of life, including labor, infrastructure and political structures. The transition to a new energy source offers a way to think about how the world is changing, and how our lives are shaped by the energy we use, Jones said.

“The nineteenth-century U.S. whale oil industry operated on a different scale than petroleum eventually would; it was smaller, less politically powerful than oil, its applications less extensive and varied, its product, whale oil, less ubiquitous in everyday life of the nineteenth century than petroleum would become in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries,” she wrote.

Even though the whaling and petroleum industries were vastly different, the early fossil fuel industry was shaped by whaling. Whalemen moved to jobs in the oil fields, and the language and imagery of whaling was used to describe oil drilling. Both industries supplied the demand for lighting oil, and, during the transition from one to the other, energy became a system and a segment of the economy, Jones said. Thinking about the dangers of whaling can help us focus on the dangers of fossil fuel production, she said.

“The violence of whaling is so clear. The violence of oil extraction and the violence of climate change isn’t as immediate and spectacular. Climate change is slow violence. I think it’s really important to pay attention to the way fossil fuel extraction and climate change harm people,” she said.

Courtesy Jamie L. Jones

The whaling ship Progress was exhibited at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The ship sailed from New Bedford, Massachusetts, to the Great Lakes and eventually to Chicago to tell the history of whaling and, in particular, whalers’ contact with Indigenous people in the Arctic. The exhibition of the whaling ship was in many ways a flop: In an exposition dedicated to new technology like steam engines, the old whaling ship was of little interest, Jones said.

Jones was inspired to research the whaling industry by her love of “Moby-Dick.” She views the novel as a work of energy theory – a critique of extractive capitalism, an account of how work and life in the U.S. are profoundly shaped by it and a meditation on the looming threat of resource exhaustion.

“In 1851, when the novel was first published, ‘Moby-Dick’ embedded a sharp critique of natural resource extraction within an apocalyptic vision of the future: of what the world might look like after the ultimate extinction of whales and even humans, and, on a more local scale, what the thriving industrial whaling ports of the United States will look like when those resources and the wealth that they generated have moved on,” she wrote.

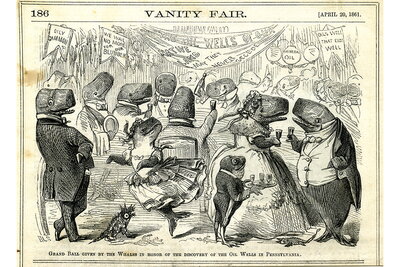

In “Rendered Obsolete,” Jones described how whaling culture became a form of entertainment. As the whaling industry declined in East Coast port towns, places like Nantucket turned to tourism and marketed their quaintness, including their whaling history, to visitors.

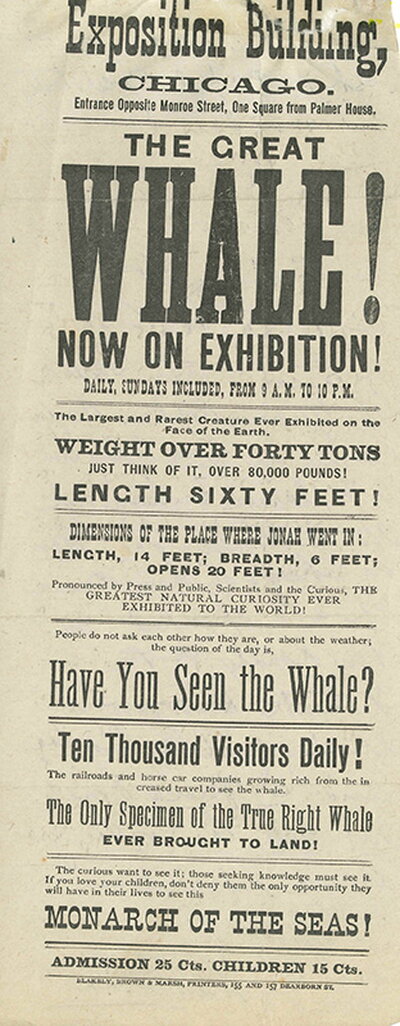

Courtesy Jamie L. Jones

Whaling entertainment extended to the Midwest and beyond in two traveling exhibitions that came to Chicago. A promoter organized a rail tour of a whale’s corpse – presented as the “Prince of Whales” – that was “in various states of decay and remediation.” Jones wrote that the dead whale tour was “perfectly continuous with the logics of animal extraction” that brought whale oil, baleen, ambergris and scrimshaws of bones and teeth far inland. A decade later, a New Bedford, Massachusetts, whaling ship sailed to Chicago as an exhibit at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, highlighting the country’s technological progress by offering a contrast between the brutality of whaling and the ostensibly clearer fossil resources powering the future, she wrote.

“Whaling nostalgia” took the form of commemorations, museums, historical writing and a film in New Bedford, which had been the center of the U.S. whaling industry. Jones focused on the racial politics of the commemorations, which portrayed whalemen as white men representing Yankee values – similar to the nostalgia with which the coal industry is portrayed today. The early 20th century commemorations intersected with white supremacy and anti-immigrant sentiment and ignored the fact that whaling crews were multiracial and included nonwhite immigrants and Black Americans who had escaped slavery, she wrote.

At the book’s end, Jones returned to “Moby-Dick” and focused on the illustrations included in the 1930 edition of the book, produced during the “Melville Revival’s” critical reassessment of the novel. Artist Rockwell Kent produced images that resembled 19th-century woodcut engravings but actually were ink drawings that “created a visual language of nostalgia for the obsolete wooden infrastructures of whaling in a form that resembles wood but which is, in fact, all style,” she wrote.

Jones sailed on the Charles M. Morgan – a former working whaling vessel that is now part of the Mystic Seaport Museum – during a 2014 exhibition trip along the East Coast that was the culmination of the ship’s restoration. Its transformation from a working whaling ship to tourist attraction encapsulates the region’s economic history, she wrote, as well as representing the infrastructure left behind by old energy systems.