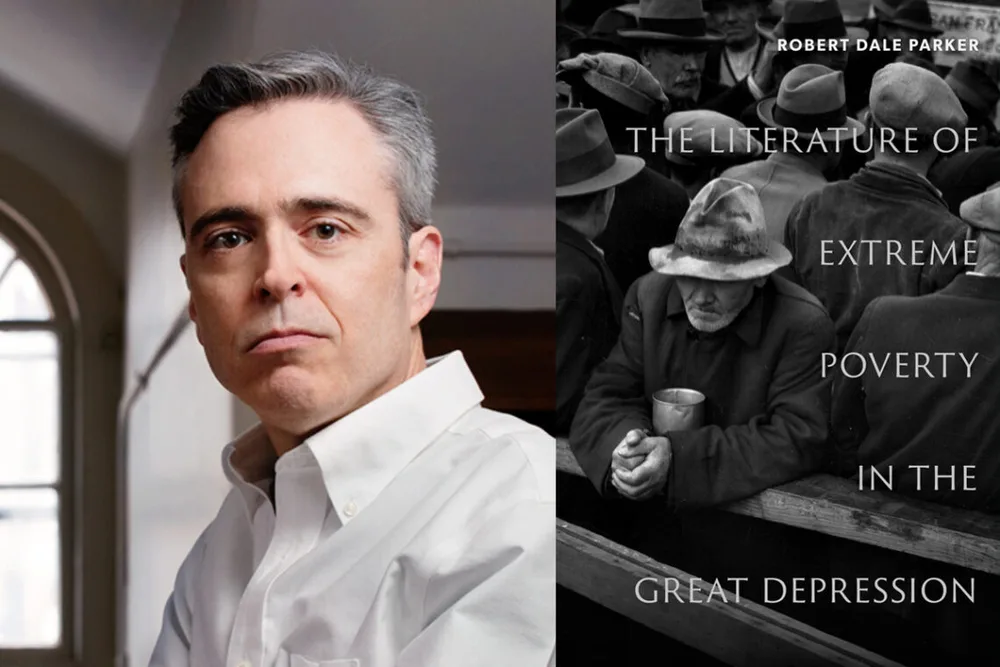

The literature of extreme poverty during the Great Depression offered an aesthetic that matched the hopelessness and isolation of the unemployed and those living on the street. Robert Dale Parker, a professor emeritus of English at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, examines what he calls “the poetics of the stiff” — the downtrodden unemployed in the forgotten literature and poetry of the 1930s — and the relationship between art and suffering in his new book, “The Literature of Extreme Poverty in the Great Depression.”

Parker focuses on lesser-known or forgotten writing that he said provides a different viewpoint of suffering than the well-known depictions of poverty in John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath” and in the documentary photographs of Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans.

“The poetics of the stiff gives us access to another and less reassuring picture of the Depression,” Parker wrote.

The documentary photographs made during the Great Depression were overwhelmingly rural, often portraying women and children. Many were made by photographers working for a federal agency, such as the Farm Security Administration, with the aim of encouraging support for the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration and New Deal programs, Parker said. They characterized their subjects as dignified and resilient, rather than hopeless. The writing examined in his book was less about offering solutions than about recognizing suffering, he said.

The 1930s movement for proletarian literature, describing the struggles of the working class, likewise left out those who couldn’t find work in a time of massive unemployment, he said. The writing he explored in his book “is the literature of people who couldn’t work, who were out on the street and didn’t know where they might find their next meal or where they would find a place to sleep that night.”

Parker’s book analyzes the Tom Kromer novel “Waiting for Nothing,” featuring an unemployed man trying to survive on the streets. The book received rave reviews when it was published, then disappeared. Parker also looks at the poetry of Langston Hughes, specifically a satirical rewrite of an advertisement for the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, and the work of Dorothy West and Martha Gellhorn, both of whom wrote stories based on their experiences as relief workers.

While focusing on these authors in the book, Parker read all the novels, stories, poems and political cartoons he could find that dealt with extreme poverty. Looking at them collectively allowed him to find repeated patterns that distinguished them from other literature of the time that followed a more conventional style, he said.

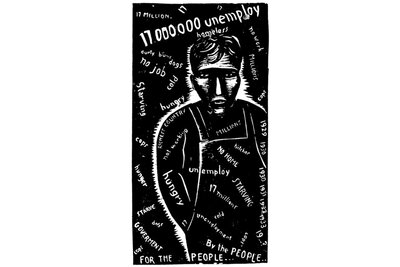

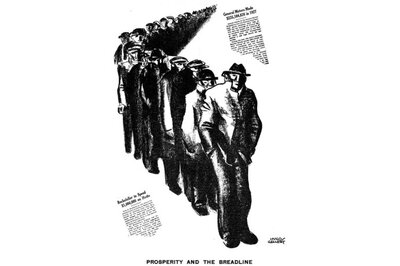

Their subject matter included people begging for food or money and the hardships they faced, such as getting ejected from a restaurant or other public places or getting beaten by the police. It also included standing in breadlines and soup lines, evictions, sleeping in flophouses, and seeking food and shelter at evangelical missions and being pressured to declare oneself saved in return. An overlooked motif that figures prominently in the Kromer novel is ostensibly straight men selling sex to queer men in exchange for food or shelter, Parker said. For those on relief, the literature depicted their terror at losing their assistance if they earned even a small amount of money at odd jobs, he said.

The literature had a characteristic form that illustrated the stagnation of time, Parker said. The repetition of the various motifs of extreme poverty became a form of frozen time.

“Standing for hours and hours and hours in breadlines makes it seem as though time has stopped. Having to beg for a meal day after day, over and over without feeling you’re making any progress, makes it seem as though time has stopped,” he said. It’s a counterpoint to “the American and modernist ideology of time moving forward, moving faster, and things getting better. The Depression hits and all that comes to a halt for millions of people.

“That is part of the pathos. There is no happy ending. This is a book about despair,” he said.

The literature also shared a direct, spare writing style similar to that of Ernest Hemingway, the lack of growth or maturation of the characters and the absence of a plot that moves forward. Parker described the intense language and present-tense narration of “Waiting for Nothing” as inventing a new style to portray the “slow crisis” of Depression poverty.

“'Waiting for Nothing’ offers an extravaganza of refusal that leaves traditional readers waiting, in effect, for nothing, like the hungry and cold narrator. … Instead of the development of character, plot, place, and time, ‘Waiting for Nothing’ offers stasis and repetition,” he wrote.

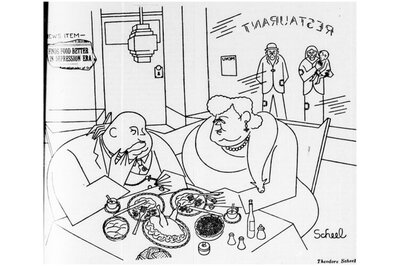

Parker wrote that the documentary photography of the Great Depression rarely showed the poor next to the wealthy and implicitly relegated the causes of poverty to supposedly natural events such as drought and crop failure. In contrast, the poems and political cartoons that Parker examined “make fun of the wealthy who look on poverty with complacency or oblivion. The cartoons portray people eating a big meal and somebody else who is starving is looking at it.”

They expressed a sense of vulnerability that the reader or viewer could soon be in the same crisis as the impoverished, he said.

The focus on the literature of the worker in the 1930s made it harder to see the portrayals of extreme poverty, and it reinforced society’s habit of looking away from the poverty that surrounds us, Parker wrote. The literature of extreme poverty allows us to see Depression suffering more directly and provides a history of the literature of a nation in crisis.

Editor's note: This article was originally published by the Illinois News Bureau. To see other recently published books, visit our faculty publications page.